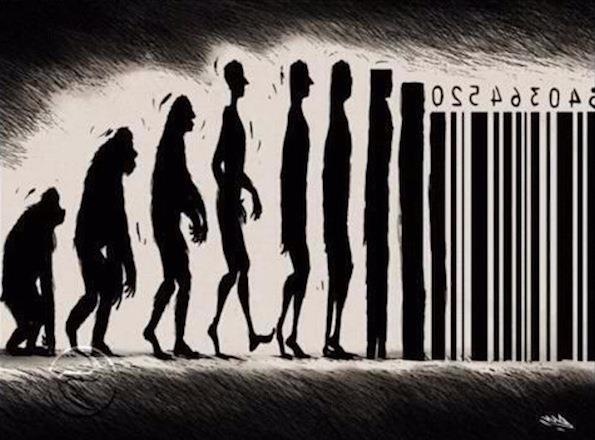

Barcode-Sequencing

A DNA barcode is a string of nucleotides, usually at a defined location in a cell genome, that can represent any feature of that cell, such as a synthetic gene deletion, an engineered exogenous operon, or a naturally-occurring genotype. Because barcodes are usually short, relative abundances of barcoded cell pools can be cheaply assayed using short-read Illumina sequencing. Barcodes can be generated to be distant from each other in sequence space, meaning that sequencing errors do not translate to errors in barcode identification, and barcodes present at frequencies lower than one in a million can be reliably measured. Barcodes are also an important form of biological data compression, whereby much longer pieces of DNA (up to an entire genome) is compressed down to 20-30 nucleotides. Because of these features, barcode-sequencing (bar-seq) has the potential to become a platform technology that can be used to answer many biological questions at extremely high throughput. One major challenge to making this happen is devising tools and methods that allow diverse sets of biological questions to be translated into bar-seq assays. Our lab has developed a "landing pad" technology that allows multiple barcodes to be inserted in tandem into a common location of a cell's genome and a toolkit by which to pair these barcodes with longer DNA elements. We are currently using this platform to study evolutionary dynamics, protein-protein interactions, genetic interactions, and segregating variation, and we think that these applications only scratch the surface of what can be done. A second challenge for advancing bar-seq as a platform technology is in developing quantitative, standardized, and reproducible methods that are easily accessible to most labs. Our work in this area is focused on developing computational tools for barcode sequencing pipelines, replicable methods of fitness estimation in complex cell pools, standardized primer sets, and spike-in controls that allow for assay performance evaluation. We are embarking on several new projects to explore this topic. Please contact Sasha if you are interested.

People: Xianan Liu, Fangfei Li, Takeshi Matsui

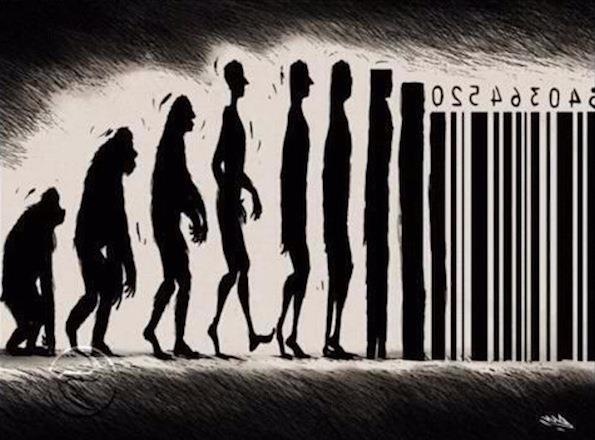

Evolutionary Dynamics

Many diseases, such as microbial infections and cancer, are driven by cell populations that evolve within a host. In many cases, these cells are of clonal origin, reach large population sizes (millions to trillions of cells), and compete over short timespans (<1000 generations). Improving our ability to forecast the dynamics of these situations could potentially result in better diagnoses, treatments, and outcomes of disease. To do this, we evolve yeast populations in the lab and combine barcode lineage tracking, sequencing of adaptive clones, and mathematical modelling to analyze evolutionary outcomes. We have found that high resolution lineage tracking can be used to estimate the distribution of beneficial fitness effects and the mutational spectrum of adaptation-driving mutations, and that these two measures can be combined to forecast the early dynamics of adaptive genetic diversity. Current efforts in the lab are focused on understanding how epistasis between adaptive mutations impacts evolutionary trajectories and population dynamics.

People: Fangfei Li, Xianan Liu

Network Dynamics

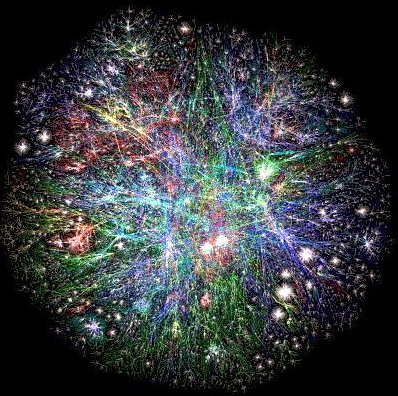

Cells are composed of many interacting genes and gene products which ultimately work in concert to determine cell phenotype. There has been a tremendous effort over the past 25 years to fully describe these interaction networks in yeast. For example, the Synthetic Genetic Array and Yeast Two-Hybrid technologies have been used to nearly completely characterize all genetic and protein-protein interactions. These studies have been a cornerstone of molecular systems biology and have contributed insights into the cellular architecture, the biological functions of genes, and the mechanisms of phenotypic robustness. Yet, largely due to the great time and cost required to carry out a comprehensive interactome screen, most interactions have been tested in a single environment and a single genotype, resulting in only a partial view of how these networks behave across the range of naturally occuring genotypes and environments these cells will encounter. Moving beyond this static view of cell networks requires technological advances to increase the throughput and ease of replication in these assays. We have developed a general interaction-Sequencing platform (iSeq), which allows millions of interactions to be screened in parallel using growth of complex cell pools and barcode-sequencing as the output. We are applying this technology to understand how genetic interactions and protein-protein interactions change across environments and genotypes. We are currently focused on adapting the Protein Fragment Complementation and CRISPR interference assays for use with our platform. We are currently hiring postdocs to work on an NIH funded project to use these tools to understand how genetic interaction evolve. Please contact Sasha if you are interested.

People: Xianan Liu, Darach Miller, Kieran Collins, Po-Hsiang Hung

High-Throughput Quantitative Genetics

The field of quantitative genetics focuses on mapping the genetic underpinnings of complex phenotypic traits and has far-reaching applications, such as improving crop and livestock yields, bioproduction, and disease prevention. The most common tools used in the field are Quantitative Trait Locus (QTL) mapping and Genome-Wide Association Mapping Studies (GWAS), which sequence many genomes and associate certain alleles with phenotypic traits. A major challenge is that these studies are generally underpowered and have difficulty identifying all the genetic loci that influence a trait. Even if all loci can be located, these studies are often unable to identify the exact polymorphism within a locus that is responsible the trait, requiring lengthy follow-up experiments. We are collaborating with the lab of Ian Ehrenreich to build next-generation barcode-based tools to improve the power and throughput of these assays. We are using these tools to explore a diverse set of questions related to the genetic architecture and evolvability of the cell. We are embarking on several new projects to explore this topic.

People: Takeshi Matsui

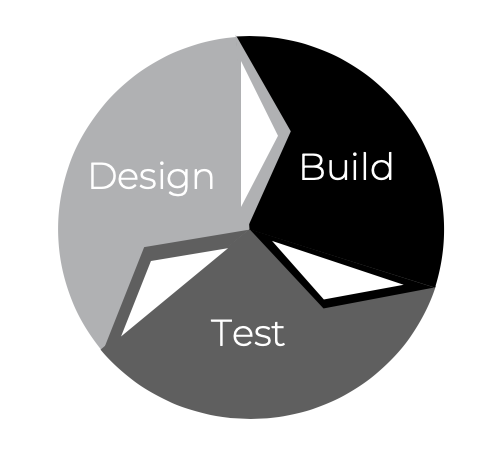

Synthetic Biology

A new direction for the lab is in the area of synthetic biology. We are biulding coupled gene assembly and design testing technologies that will speed up and parallelize the design build test cycle of synthetic biology. We aim to use these technologies to recode bacterial and yeast genomes. We have two available positions for DOE-funded work in this area. Please contact Sasha if you are interested.

People: Xianan Liu, Weiyi Li